Forty years ago, the Coen brothers’ first film set the tone for their filmography. Here’s why you should watch it now

simple blood is a gloriously clean and well-constructed dark comic noir that walks the line between pure satire and absolute nihilism. Forty years after its release in January 1985, the Coen brothers’ first film remains one of the defining debut films of the last half-century. Like Athena emerging fully formed from the head of Zeus, all of Coen’s motifs were perfectly formed from the get-go.

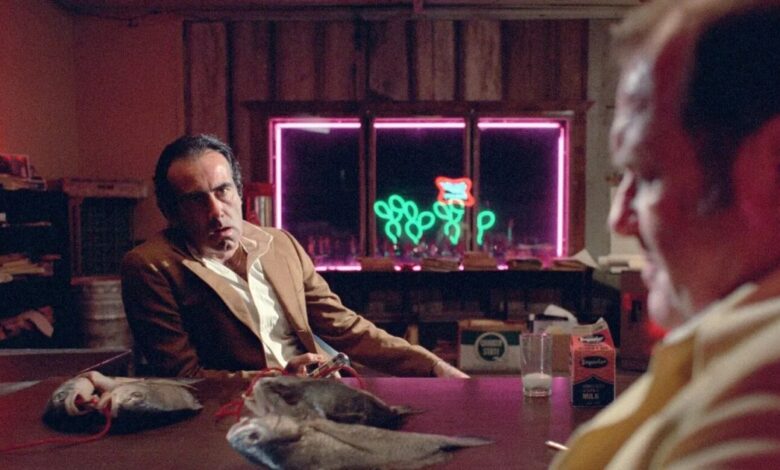

A beautiful visual language

Like all Coen films before 2004. The lady killers, simple blood Joel Coen officially ordered him to comply with DGA regulations at the time that allowed only one credited director on a project. But the brothers have always directed, written, produced and edited their films together, and simple bloodwith its stylized shots (a view down the barrel of a discarded gun, two lovers framed in a huge arched window) it is, like all his films, a succession of perfect images, gilded in neon purples and deep, dark blues. With cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld, himself later an accomplished director (from 1991 The Addams Familyamong others), the Coens create a parade of painting-like frames almost surprising for their incessantness, clearly influenced not only by classic film noir but also by more or less contemporary films such as that of Terrence Malick. days of heavenwith its strange feeling of the big sky of the American West.

Joel Coen and Frances McDormand

The film is notable for the formation of one of Hollywood’s most enduring power couples: director Joel Coen and his future wife, star Frances McDormand, met at their audition. Unsurprisingly, as with everything McDormand appears in, the film belongs to her. For the uninitiated, what will be most surprising is the degree to which she sneaks up on the story, taking over suddenly and without warning after a slow start. She plays Abby, the unhappy wife of Texas bar owner Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya, an outsider with a New York accent). In the first scene, she leaves her husband and travels with her employee, Ray (John Getz). In the rain-soaked car sequence that plays below the credits, the Coens already introduce the visual theme that repeats throughout the film, such as a nearly epilepsy-inducing passing of shadows that obscures Getz and McDormand further. beyond the point of recognition. If the people in this film ever really see each other, it is only sporadically and in tiny flashes; It’s no surprise, then, that many of the later scenes are obscured by the shadows (or shot through the blades) of the ubiquitous ceiling fans. .

The role of comedy.

Ray and Abby end up in bed in a hotel room, where they will be surreptitiously photographed by the extraordinarily sweaty private detective Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh), whom Marty has hired to follow them. Marty, tormented by jealousy, hires Visser to kill them both. Visser, although clearly a nobody with his nasty Volkswagen bug and hand-rolled cigarettes, takes the job. What follows is enough misunderstanding for a French farce, in which none of the participants are particularly trustworthy, although some are creepier than others. Not surprisingly, Visser spends much of the film, including its climactic final scene, laughing uncontrollably. The film is careful to take its characters seriously, but some of this stuff is inescapably funny: Visser, Ray, and Marty are all different shades of stupid and, for the most part, too weak-minded to function as the cold-blooded killers. which results. they will have to be. Thematically, we’re setting ourselves up with a foundation of a cinematic mentality that the Coens would bring to even the most serious of their later films (even their cold butcher knife masterpiece, It’s not a country for old people) — beneath the best-laid plans of violent men runs a constant undercurrent of cosmic irony.

Future Coen collaborators

All future regular members of the Coen group are, like their directors, firing on all cylinders from the start. Carter Burwell, who would write music for all but one of the films the Coens made from 1985 until their seemingly temporary (but still ongoing) breakup in 2018provides a synth and piano score that sounds like a series of sonar messages emerging from the depths of the ocean. Walsh, who would appear in the Coens’ second film, Raising or unfinished business that needs to be resolvedadopts a delightfully unintelligible Southern accent to create a character alternately turgidly callous (a fly seems to always be buzzing around his forehead) and chillingly determined. (There’s even a cameo from the future Raising Arizona and Oh brother, where are you? star Holly Hunter, as voice over phone.)

McDormand steals the show

But once again, the film belongs to Frances McDormand, whose Abby Marty spends much of the film unaware of the ill-formed machinations of the men in her life and with whom reality collapses only in the final scene of the film. film, which she plays. to perfection. There’s an element of Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode in McDormand’s Abby as she undertakes her final showdown against Visser in the spare apartment she rented to escape her husband. She sweats too (everyone in this movie always sweats in the oppressive Texas heat), backs up against the walls, and sinks shakily to the floor, a gun shaking in her hand. But his fiery eyes are inflexible. Julian Marty, Visser and Ray are fascinating figures from a noir perspective: like many of their genre forebears, they seem to be implementing every safeguard possible to prevent their plans from falling apart, but they constantly make obvious mistakes, leaving evidence of their embezzlement. . In the last fifteen minutes of the film, Abby, on the other hand, is the closest thing the story has to an action hero, climbing up the sides of buildings, firing off well-timed shots, and acting as the focal point of a magnificently staged piece. of violence that I will not spoil here. As in the case of the Coens fargo (1996), in which McDormand plays a Minnesota police officer who only needs a momentary glance at a crime scene to fully understand everything that happened, McDormand is the smartest woman in the room. It seems correct to me.

a perfect ending

Of course, even Abby’s victory is based on the same circumstances that guide almost everything in simple blood — misunderstanding. (Even when he confronts Visser, he thinks he’s Marty.) In the final shot of the film, Visser, though not triumphant, laughs once again, both at himself and at Abby. How stupid these mortals are.

simple blood is transmitting max..